“It was easy for the Nazis to kill Jews, because they did it. The allies

considered it impossible and too costly to rescue the Jews, because they didn't

do it. The Jews were abandoned by all governments, church hierarchies and

societies, but thousands of Jews survived because thousands of individuals in Poland, France, Belgium, Denmark, Holland helped

to save Jews. Now, every government and church says, "We tried to help the

Jews", because they are ashamed, they want to keep their reputations. They

didn't help, because six million Jews perished, but those in the government, in

the churches they survived. No one did enough."

Jan Karski during

an interview with Hannah Rosen in 1995.

In August 1944 when Allied planes bombed the IG Farben

plant, Eli Wiesel, noted author and survivor of Auschwitz who was

imprisoned in Buna-Monowitz (Auschwitz III), the slave-labor camp of Auschwitz.

Wiesel later recalled the event by writing;

“We were no longer afraid of death;

at any rate, not of that death. Every bomb filled us with joy and gave us new

confidence in life.”

For nearly three decades the failure to bomb Auschwitz during

the Second World War and the Holocaust was a minor side issue rarely discussed.

It was not until American historian David Wyman wrote an article in the

magazine Commentary of May 1978 titled “Why Auschwitz Was Never

Bombed” was the issue awoken. His article included the startling photographs

published by two leading Central Intelligence Agency photographic interpreters,

Dino Brugioni and Robert Poirier.

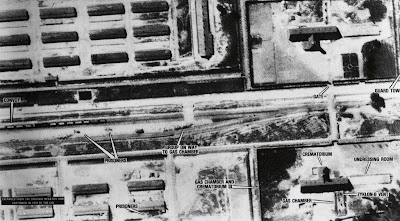

Allied aerial reconnaissance units under the command of the 15th U.S. Army Air Force took photos during missions dating between April 4, 1944 and January 14, 1945. A typical sortie employed two cameras equipped with lenses of different focal lengths. The photos were used to plan bombing raids, determine the accuracy of bombing sorties, or make damage assessment. These 1944 US Air Force photos were

redeveloped with technology available in 1978 gave a vivid demonstration of

what U.S. intelligence

could have known about Auschwitz-Birkenau, if only they had been interested.

One of these photographs clearly shows bombs dropping over

the camp—because the pilot released the bombs early, it appeared that bombs

targeted for the Farben plant were dropped on Auschwitz-Birkenau. Other

pictures reveal rows of Jews on the way to the gas chambers. Wyman's claims

gained considerable attention, and the failure to bomb became synonymous with

American indifference.

Aerial reconnaissance photograph of Auschwitz II–Birkenau extermination camp in German-occupied Poland taken in September 1944 during one of four bombing missions conducted in the area. Enlargement shows bombs intended for an IG Farben factory falling over gas chambers II and III.

The often asked question; “Why wasn't Auschwitz bombed?” Is not only a historical question but it is also a extremely moralistic question symbolic of the lack of Allied military response to the plight of the Jews during the Holocaust. The issue was launched in the late 1970s when aerial reconnaissance films, which had never been developed or seen by anybody during the war, were found by Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) analysts to show that U.S. bombers had flown over Auschwitz-Birkenau on their way to and from bombing other targets.

The first time an American president had ever explicitly

acknowledged the refusal of the U.S. to

take military action to disrupt the mass murder process was at the delivery of

the keynote address at the opening of the United

States Holocaust Memorial Museum,

in Washington, D.C.,

on April 22, 1993.

President Bill Clinton said the construction of the museum would “redeem in

some small measure the deaths of millions whom our nations did not, or would not,

or could not save.” President Bill Clinton referred to America’s

lethargic response to the Holocaust as constituting “complicity” in what

happened. “For those of us here today representing the nations of the West, we

must live forever with this knowledge--even as our fragmentary awareness of

crimes grew into indisputable facts, far too little was done,” the president

said. “Before the war even started, doors to liberty were shut and even

after the United States and

the Allies attacked Germany,

rail lines in the camps within miles of militarily significant targets were

left undisturbed."

The former Foreign Minister of Poland Władysław Bartoszewski

in his speech at the ceremony of the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the

concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 27 January 2005, said: "The Polish resistance

movement kept informing and alerting the free world to the situation. In

the last quarter of 1942, thanks to the Polish emissary Jan Karski and his

mission, and also by other means, the Governments of the United

Kingdom and of the United

States were well informed about what

was going on in Auschwitz-Birkenau."

Auschwitz-Birkenau “The Death Camp”

Auschwitz was the largest camp

established by the Germans. It was a complex of camps, including a

concentration, extermination, and forced-labor camp. It was located at the town

of Oswiecim near the

prewar German-Polish border in Eastern Upper Silesia,

an area annexed to Germany in

1939. Auschwitz I was the main camp and the

first camp established at Oswiecim.

Auschwitz II (Birkenau) was the killing center at Auschwitz.

Trains arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau almost daily with transports of Jews from

virtually every German-occupied country of Europe.

Auschwitz III, also called Buna or Monowitz, was established in Monowice to

provide forced laborers for nearby factories, including the I.G. Farben works. At

"least" 1.1 million Jews were killed in Auschwitz. Other

victims included between 70,000 and 75,000 Poles, 21,000 Roma, and about 15,000

Soviet prisoners of war.

Auschwitz was the largest camp

established by the Germans. It was a complex of camps, including a

concentration, extermination, and forced-labor camp. It was located at the town

of Oswiecim near the

prewar German-Polish border in Eastern Upper Silesia,

an area annexed to Germany in

1939. Auschwitz I was the main camp and the

first camp established at Oswiecim.

Auschwitz II (Birkenau) was the killing center at Auschwitz.

Trains arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau almost daily with transports of Jews from

virtually every German-occupied country of Europe.

Auschwitz III, also called Buna or Monowitz, was established in Monowice to

provide forced laborers for nearby factories, including the I.G. Farben works. At

"least" 1.1 million Jews were killed in Auschwitz. Other

victims included between 70,000 and 75,000 Poles, 21,000 Roma, and about 15,000

Soviet prisoners of war.

The capacity to hit targets in Silesia (where

the Auschwitz complex was located) by the 12th Air force

was possible as evidenced by the reconnaissance photos in July 1944. US

and British officials decided not to bomb Auschwitz based

on the technical argument that their aircraft did not have the capacity to

conduct air raids on such targets with sufficient accuracy, and in part with a

strategic argument that the Allies were committed to bombing exclusively

military targets in order to win the war as quickly as possible.

As early as May 1944 the U.S. Army Air Forces had the

capability to strike Auschwitz at will. The

rail lines from Hungary were

also well within range, though for rail-line bombing to be effective it had to

be sustained. On July 7, 1944,

American bombers flew over the rail lines to Auschwitz.

On August 20, 127 B-17s,

with an escort of 100 P-51 fighter craft, dropped 1,336 500-pound bombs on the

IG Farben synthetic-oil factory that was less than 5 miles (8 km) east of Birkenau. German oil

reserves were a priority American target, and the Farben plant ranked high on

the target list. The death camp remained untouched. It should be

noted that military conditions imposed some restrictions on any effort to bomb Auschwitz.

For the bombing to be feasible, it had to be undertaken by day in good weather

and between July and October 1944.

There are those who claim that the question of bombing Auschwitz first

arose in the summer of 1944, more than two years after the gassing of Jews had

begun and at a time when more than 90 percent of the Jews who were killed in

the Holocaust were already dead. These detractors claim that it could not have

arisen earlier because not enough was known specifically about Auschwitz,

and the camps were outside the range of Allied bombers.

However the truth is, as I mentioned in the quote by the

former Foreign Minister of Poland Władysław Bartoszewski in his speech, that

in 1942 a World War II Polish resistance movement fighter Jan Karski

had reported to the Polish, British and U.S. governments on the

situation in Poland, especially on the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto

and the Holocaust of the Jews. He had also carried out of Poland a

microfilm with further information from the underground movement on the

extermination of European Jews in German-occupied Poland.

The Polish Foreign Minister Count Edward Raczynski provided the Allies on this

basis one of the earliest and most accurate accounts of the Holocaust. A note

by Foreign Minister Edward Raczynski entitled The mass extermination of Jews in

German occupied Poland,

addressed to the governments of the United Nations on 10 December 1942, would later be published along

with other documents in a widely distributed leaflet

Karski met with Polish politicians in exile including the

Prime Minister, as well as members of political parties such as the Socialist

Party, National Party, Labor Party, People's Party, the Jewish Bund and Poalei

Zion. He also spoke to the British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, giving a

detailed statement on what he had seen in Warsaw and

Bełżec He then traveled to the United States and

reported to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In July 1943 Karski again

personally reported to Roosevelt about the

situation in Poland.

With the German invasion into Hungary in

March 1944 the Nazis confined the Hungarian Jews to ghettos. Between May 15 and

July 9, the Nazis deported some 438,000 Jews on 147 trains from Hungary to

the death camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. To accommodate the large quantity of

newly arriving Hungarian Jews, the Nazis built a special railroad spur directly

into Auschwitz-Birkenau.

At this time the Free Polish Underground sent the Allies

more explicit information about the process of mass murder from eyewitness

testimony that the Nazis were sending four of the five arriving Jews directly

to their death. On some days as many as 10,000 people were murdered in its

gas chambers as the extermination camp was strained beyond capacity. The

Auschwitz-Birkenau gas chambers were now operating around the clock, and the

crematoria were so overtaxed that bodies were being burned in pyres in open

fields with body fat fueling the flames.

Given here below is US Air Force Recon photographic proof of a huge transport of some 85 boxcars is present at the Birkenau rail-head. Details of the compound, including the expansion into Section III necessitated by the large influx of Hungarian Jews, were observed.

A large column of prisoners, estimated at some 1,500 in number, is seen marching on the camp's main north south road. There is activity at Gas Chamber and Crematorium IV, and its gate is open; this may be the final destination of the newly arrived prisoners. In Auschwitz I, we have the other part of the drama, those sent "to the right," being enacted at Birkenau.

In front of the Main Camp Registration Building, a long line of prisoners is visible. This was undoubtedly the group spared death in the gas chambers but condemned to a living death in an SS work detail. They stand frozen in time, awaiting their tattoos and work assignments.

The prisoners sent "to the left" were deceived into thinking they were going to be showered and disinfected. After undressing in an anteroom, they were herded into the shower/gas chamber and put to death by means of Zyklon-B gas crystals introduced into the chamber through exterior vents. The bodies were then moved to the crematoria or external burning pits for disposal.

Approximately 310,000 out of the 438,000 Hungarian Jews

where murdered by the Germans immediately upon arrival at the

killing center between May 15 and July 11, 1944 a period of only 57 days or 5400

Jews exterminated per day.

In desperation, Jewish organizations made various proposals

to halt the extermination process and rescue Europe's

remaining Jews. A few Jewish leaders called for the bombing of the Auschwitz gas

chambers; others opposed it both sides feared the death toll or the German

propaganda that might exploit any bombing of the camp's prisoners.

It is important to note that before the summer of 1944, Auschwitz was

not the most lethal of the six Nazi extermination camps.

In actuality at

Treblinka the Nazis had exterminated 750,000 to 900,000 Jews in the

17 months of its operation, or some 1780+ Jews per day

At

Belzec 600,000 Jews were exterminated in less than 10 months or some 2000 Jews

per day. The Nazis closed both camps these camps with the completion of their

mission, the destruction of Polish Jewry in 1943. It was during the summer

of 1944 that Auschwitz overtook the other

death camps not only in the sheer number of Jews murdered but in the pace of

their extermination. The condition of the remaining Jews of Europe was

desperate.

In April 1944 two prisoners, Rudolf Verba and AlfredWetzler, managed to escape from Auschwitz made contact with Slovak resistance

forces and produced a substantive report made contact with Slovak resistance

forces and produced a substantive report on the extermination camp at

Auschwitz-Birkenau in great detail. They had documented the extermination

process, replete with maps and other specific details. This was forwarded to

Western intelligence officials along with an urgent request to bomb the

extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Once more the Polish Underground had provided information

that they gave to the Allies together with intelligence gained from two other

prisoners who had managed to escape shortly afterwards. This information became

known as the "Auschwitz Protocols".

The report, forwarded to the U.S. government's

War Refugee Board by Roswell McClelland, the board's representative in Switzerland,

arrived in Washington between

July 8 and July 16, 1944.

The complete report, together with maps, did not arrive in the United

States until October, since U.S. State

Department representatives “neglected” to mark the material as

urgent.(see President Clinton's statement of "Complicity")

This was the first absolute and conclusive proof the

Allies received that mass murder was taking place at Auschwitz.

Limited information about the camp had reached the West before this date, but the

Auschwitz Protocols removed any reasonable doubt about the scale and nature of

the crime, and the Western media were quick to report the news. On 18 June the

BBC broadcast a radio story about Auschwitz, and on

20 June the New York Times carried a report which explicitly mentioned the ‘gas

chambers’ at Auschwitz/ Birkenau.

With the disclosures from Karski, Secretary of the Treasury,

Henry Morgenthau Jr. together with his subordinate officials, demanded in

late 1943 to remove responsibility for the refugee and rescue issues from the State

Department- (Why was this done?)- in

favor of an independent agency. At the same time, the Emergency Committee to

Save the Jewish People of Europe, one of the major Jewish rescue organizations,

persuaded a dozen influential Congress members to support such a move.

Additional support and public interest consequently accumulated, and

legislation seemed imminent.

Until early 1944, the Roosevelt administration

declared policy was "rescue through victory," that is,

rescue of Jews could only be accomplished through a military victory over the

Germans on the battlefield.

Suddenly with these disclosures FDR issued an Executive

Order on January 22, 1944 creating

a War Refugee Board officially headed by the Secretaries of Treasury, State and

War. Avoiding direct mentioning of “Jews”, the presidential Executive

Order creating the WRB authorized it “to take all measures within its

power to rescue the victims of enemy oppression who are in imminent danger of

death and otherwise to afford such victims all possible relief and assistance

consistent with the successful prosecution of the war.” The order directed

all government agencies, and in particular the State, Treasury and War

Departments, to provide the Board with whatever help it needed in fulfilling

its mission. The Treasury Department housed the WRB and provided most of its

staff, including its executive director, John W. Pehle.

In the War Department, because Secretary of War H.L.Stimson

could spare almost no time out of his regular wartime duties, the

responsibility in respect of the Board was relegated to his assistant, John J.

McCloy, who in private was skeptical that the military should play a role in

rescue efforts.

The Vrba-Wetzler report provided a clear picture of life and

death at Auschwitz. As a result, Jewish leaders in Slovakia,

some American Jewish organizations, and the War Refugee Board all urged the

Allies to intervene. However, the request was far from unanimous. Jewish

leadership was divided. As a general rule, the established Jewish

leadership was reluctant to press for organized military action directed

specifically to save the Jews. They feared being too overt and encouraging

the perception that World War II was a “Jewish war.” Zionists, recent

immigrants, and Orthodox Jews were more willing to press for specific efforts

to save the Jews. Their voices, however, were more marginal than those of the

established Jewish leadership, and their attempts were even less effective.

By June 1944 information concerning the camps and

their function was available—or could have been made available—to those

undertaking the mission. German air defenses were weakened, and the accuracy of

Allied bombing was increasing. All that was required was the political

will to order the bombing.

In 1944 the World Jewish Congress implored the American

government to bomb Auschwitz. In August, Assistant

Secretary of War John J. McCloy wrote to Leon Kubowitzki of the World Jewish

Congress, noting that the War Refugee Board had asked if it was possible to

bomb Auschwitz. McCloy responded:

After a study it became apparent that such an operation

could be executed only by the diversion of considerable air support essential

to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations elsewhere and

would in any case be of such doubtful efficacy that it would not warrant the

use of our resources. There has been considerable opinion to the effect that

such an effort, even if practicable, might provoke even more vindictive

action by the Germans.

The War Department had decided in January that army

units would not be “employed for the purpose of rescuing victims of enemy

oppression” unless a rescue opportunity arose in the course of routine military

operations. In February an internal U.S. War Department memo stated, “We

must constantly bear in mind, however, that the most effective relief which can

be given victims of enemy persecution is to insure the speedy defeat of the

Axis.” This was the internal policy of the Roosevelt administration

to reject all the requests because it was opposed to diverting any military

resources for humanitarian objectives from victory in the war effort.

There are those who assume that anti-Semitism or

indifference to the plight of the Jews—was the primary cause of the refusal to

support bombing, this may have been however the issue is much more complex. In

a meeting of the Jewish leadership in Palestine embodied

in the Jewish Agency executive committee, met on June 11, 1944 in Jerusalem and

refused to call for the bombing of Auschwitz.

Chairman of the executive committee David Ben-Gurion, said, “We do not know the

truth concerning the entire situation in Poland and

it seems that we will be unable to propose anything concerning this matter.”

Once the Vrba-Wetzler report arrived in Palestine, along

with new information from the Zionistic Partisans and members of the Socialist

Bund movement over the pace and extent of extermination. Ben-Gurion and the

Jewish Agency executive committee had come to understand what was happening in Poland and

they were forcefully calling for the bombing by July.

Jewish Agency officials appealed to British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill, who told his foreign secretary Anthony Eden on July 7, “Get

anything out of the Air Force you can and invoke me if necessary.” Similar

requests were also made to American officials to bomb Auschwitz.

At the same time that the Jews were asking for the bombing

of Auschwitz the Free Polish Army and

underground were begging for aid in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 by bombing

the city.

Yet the Americans denied the requests to bomb Auschwitz,

citing several reasons: military resources could not be diverted from the war

effort (as they were to support the non-Jewish Poles); bombing Auschwitz might

prove ineffective; and bombing might provoke even more vindictive German

action. On the other hand, the Americans did not evoke the claim that Auschwitz was

outside the range of the most effective American bombers.

Military historians have challenged Holocaust historians in

an ineffectual debate whole books have been written in recent years arguing

about the practicalities of bombing Auschwitz.

There is a general expert consensus that there would have been little point in

bombing the railway lines to Auschwitz since the

Nazis would have simply diverted the transports to another track or found

alternative means of getting the Jews to the camp.

So "What IF" if the gas chambers II and III would

have been destroyed?

The Germans had two previous gas chambers – known as

Bunker 1 and Bunker 2 – which pre-dated these larger killing factories

which were still available for use at Auschwitz/Birkenau that

the Auschwitz Protocols had not mentioned

Bunker 1 and Bunker 2 would therefore not have been

destroyed by any Allied bombing attempt, and they offered all the killing

capacity the Germans needed from the summer of 1944 onwards, since by then the

massive influx of the Hungarian Jewry had already been exterminated at

Auschwitz/Birkenau.

So the debate rages on.

"Was bombing feasible, and when?"

From what air fields would the bombers take off, and where

would they land?

What airplanes would be used?

What escorts would be required, and at what cost in men and

material?

Could lives have been saved and if so how many?

And at what cost to the Allies?

But in addition to military considerations, political

questions were at issue.

To whom and how deeply did the plight of the Jews matter?

Were Jews effective or ineffective in advancing the cause of

their brethren abroad?

Did they comprehend their plight?

Were they compromised by their fears of anti-Semitism or by

the fears they shared with American political leaders that the World War would

be perceived as a Jewish war?

Historians are uncomfortable with the counter-factual

speculation “What if…” but we still bow our heads in shame and whisper

"What if."